On the brink of exceeding the 1.5C carbon limit

And a look at sea level rise over a century, solar farm carbon storage, and more.

The climate press treats some stories as almost mandatory to cover. We saw an example of this late in the week, when myriad outlets reported that according to scientists, the world has just 3 years of global emissions left before committing to a breach of the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit.

But something interesting happened along the way to hive-mindedness. The Guardian diverged from the main line of coverage and so did France 24 (working with the AFP). They instead reported that the world has only two years left, not three, to exhaust the remaining 1.5°C emissions budget.

What’s going on here?

The answer is that with 1.5°C of warming above preindustrial levels so close now, we’re entering a weird world of carbon probabilities. It’s not that anybody’s wrong, but rather, that no single number of years may suffice to understand the current predicament.

The latest news stories are all rooted in a recent, downward scientific revision of the remaining global carbon “budget,” defined as the amount of carbon dioxide the world can emit and still remain below a given level of warming — in this case, 1.5°C (2.7°F) above pre-industrial levels. That revision came in a much broader study in Earth System Science Data by a large ensemble of climate scientists, who are now assessing the state of warming on an annual basis.

Normally, we think of a “budget” as something fixed. If your budget is $ 1,000 to the end of the month, that means you simply don’t have any more money than that to spend (or save).

The carbon budget is not like this. The key parameter that determines the carbon limit for any particular temperature — the transient climate response to cumulative emissions — is somewhat uncertain. So there is no single value to the remaining carbon budget, and no single number of years of emissions that we have left.

“The way the carbon budget is defined does not really map to this ‘we have X years left,’” said Glen Peters, a scientist at the Center for International Climate Research in Oslo, Norway, who was also a co-author of the new study, by email.

This becomes clearer when we visualize the carbon budget figures as published in the new study. Here, I show the probability of avoiding a warming of 1.5°C for each additional year of emissions at current levels (which, in 2024, were about 42 billion tons of carbon dioxide):

The “central estimate,” as scientists put it in a press release, is indeed that to hold on to a 50 percent chance of avoiding 1.5°C, we’ve got about 3 years left to change our emissions (drastically). But that doesn’t make the Guardian/France 24/AFP approach wrong — they just went with the 67 percent chance value instead. To preserve those odds, emissions must fall even faster and the math says there are only about two years remaining (to take emissions down to zero).

“Your allowance of the risk of exceedance determines what the carbon budget is,” explained Joeri Rogelj, a scientist with Imperial College London who played a central role in the assessment of the budget in the latest study.

The true takeaway is thus less about any particular number of years remaining. Rather, it is that we’re getting very, very close to depleting the budget and the risk of doing so is growing rapidly.

Indeed, as you can see on the chart, it is already possible, although not likely, that in mid-2025 the budget is depleted. Another way of putting this is that we have no time left if you desire a very high level of certainty that we can still avoid 1.5°C.

And it is not like global emissions can suddenly come to a halt in two to three years. Nobody is shutting down the world to preserve the carbon budget.

Rogelj said something very striking in our conversation about the carbon budget, and where we are now.

“We’re just peering into the mist at this stage,” he said.

We are so very close to the 1.5°C target now that we’re living and breathing within the uncertainty ranges of the carbon budget.

(And get this — the true uncertainties are larger than expressed in the chart above. You can find an additional, more sophisticated carbon budget in the supplemental materials of the new study. I won’t show any more here, but suffice it to say that if you take into account additional factors like non-CO2 gases, the uncertainty curtain further envelops the present moment. It even becomes possible that we depleted the 1.5°C carbon budget years ago.)

The acceleration of sea level rise

The carbon budget discussion is just one part of a much larger reading on the state of the warming of the climate in the latest study, which was led by Piers Forster at the University of Leeds, but represents the work of dozens of other climate scientists as well.

The news isn’t great. Emissions are still rising, the carbon budget is still shrinking. From a temperature perspective, we’re also within maybe 5 years of exceeding 1.5°C of warming. The depletion of the carbon budget for 1.5°C, and the crossing in terms of actual temperature measurements, need not happen exactly at the same time. But it is noteworthy that as we get quite close to both, you have to start squinting to see precisely where you are.

Lots of other parameters are also worsening. For instance, the study shows that sea level rise is clearly accelerating:

This is not surprising when you consider that the vast majority of the heat energy being trapped within the planet’s system is going into the oceans (which expand as a result), and a substantial fraction is going into melting polar ice — something the study also documents.

The new research does find one bit of good news, in that the rate of increase in emissions is slowing, so maybe emissions will peak soon. But I feel like I’ve been writing this forever. We’ll see if it bears out.

Climate Rundown, 6/22/2025:

A few other intriguing things I found this week:

Solar farms are also storing carbon! There doesn’t seem to have been much discussion of this really striking study in Nature Geoscience from a few weeks back. In it, researchers from a number of institutions in China, Canada, the U.S. and the UK used satellite techniques and machine learning to study where large solar farms were installed between 2000 and 2018, and what kind of land surface the installation occurred on.

And they found that, because so many installations started out on agricultural lands but then subsequently allowed grasses to grow, about 2.1 million tons of carbon (or, the equivalent of removing nearly 8 million tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere) will be stored in these areas while the solar farms do their work. Europe was the region that best epitomized this strategy.

This is important because the amount of land covered by large solar farms is expected to grow dramatically. The study estimated that from 2000 to 2018 it was under 1,500 square miles, but by 2050 it is expected to be over 20,000 square miles. So if land is managed properly, not only can solar generate electricity without fossil fuel burning, but the land used can also further mitigate global warming.

Using a trans-Atlantic cable to gather ocean data. Scientists never cease to impress with their ingenious new ways of getting data.

Take EllaLink, a more than 3 thousand mile long undersea internet cable connecting Fortaleza, Brazil, to Lisbon, Portugal. Now, scientists from Caltech, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Nokia have worked to instrument the cable so that it can be used for scientific measurements. It turns out that the strains on the cable reflects the tides and, in some places, water temperatures. In addition to providing such data, the researchers think this technique could also lead to better tsunami warnings. How cool is that?

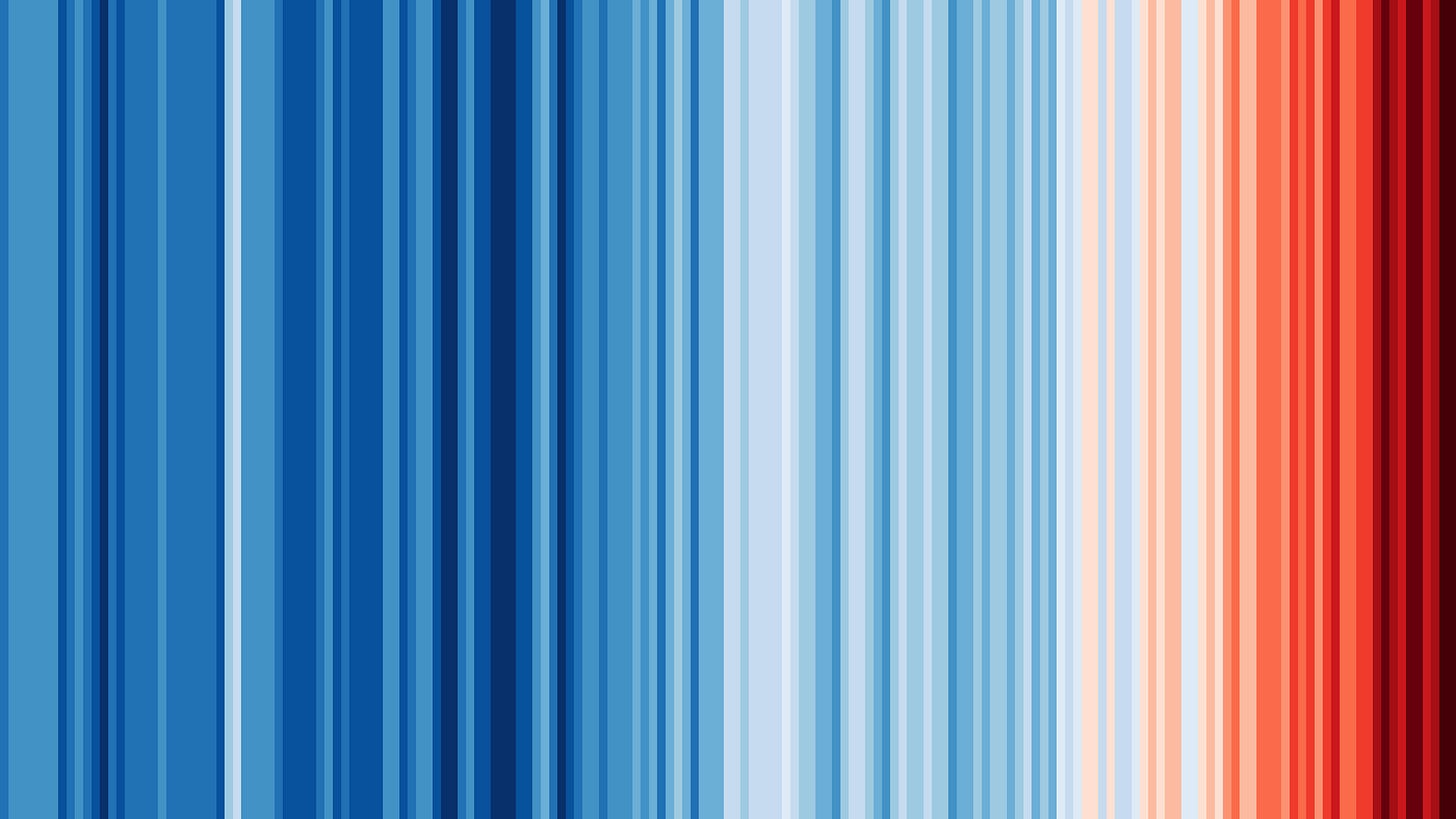

Celebrating the warming stripes. I think a lot these days about effective data visualization. It’s hard to think of a better example than Ed Hawkins’ climate stripes, which visualize temperature change using an intuitive blue-to-red color palette, and no other information. Yesterday (the 21st of June) was Show your stripes day, and I’m happy to take part with this image of the global version.

Update: I added a chart about sea level rise and some explanation after this post was originally published.

I'm with NASA GISS director Gavin Schmidt on climate countdowns (here from a Bluesky post of his): https://bsky.app/profile/climateofgavin.bsky.social/post/3ls33gjvaqc2s

"I was consulted, a while ago, on whether a clock that counted down the estimated carbon budget for 1.5°C would be a good idea.

I asked them what they planned to do when it went past zero?

I did not get an answer, and they didn’t ask me anything again. 🤷"